This is it, folks. The last chapter. Five and a half years, triple-digit classics, and—in self-congratulations—the pie party to end all pie parties.

IT’S MY PARTY AND I’LL PIE IF I WANT TO.

On my long and harrowing journey across the wilderness of my own bookshelf, I visited 30+ countries—some real, some imaginary. I met heroes, villains, God, and the devil. I went to war and fell in love and traveled through time and witnessed magic. I worried and grieved and LOLed and maybe, slightly, occasionally lost my mind.

And I wrote and wrote and wrote, trying to find it again.

I never doubted that I’d finish—mostly because I try not to make a habit of self-doubt. I’m still convinced that if I really wanted to, and worked really hard at it, I could be an Olympic triathlete, or a Mars-bound astronaut, or a turtle whisperer with my own TV show. And while that kind of certainty is probably diagnosable, it may also be the very reason I was able to finish The Challenge. Predicting how this story ended was—spoiler alert!—the easiest part.

The hardest part was, of course, everything else. The 100 Greatest Books of All Time don’t read themselves—and it was up to me, day after day, to sit down and turn pages. My best estimates suggest that I read 50,817 pages to close out The List, one determined word at a time. The shortest book on The List was 75 pages.

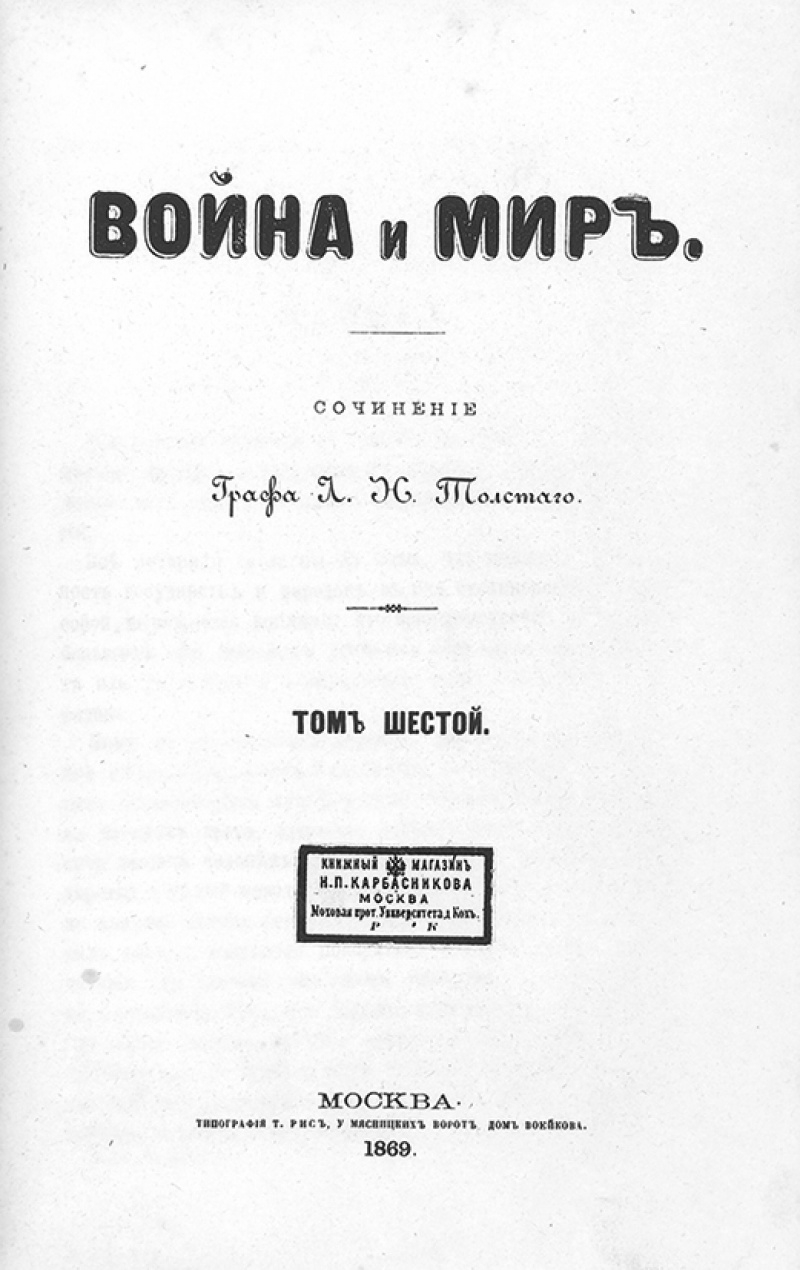

The longest was 4,217.

But it’s all over now, and I can devote my remaining lifespan to full-time snobbery. I can casually name-drop Proust, and sneer at the very idea of e-readers. I can even call myself a literary badass, if there is such a thing.

I won’t, obviously, do any of that. But I will take a moment out to shake my own hand, feather my own cap, and pat myself on the back for a mundane victory. What is life, after all, without a little revelry? Why even bother existing, without the slightest swagger?

I hope I never find out. But if I do, it will probably be in a book.

…

When I celebrate, I celebrate in lists. (Well, and pie.) Every milestone up until this point—50 books, 75 books, 80 books, 90 books—has been commemorated with at least one list, but usually several. And even though I don’t believe in tradition for tradition’s sake, I do believe in the power of lists to spread peace, love, joy, and the satisfaction of a job well-organized.

So here we go, one last time: The List, in lists.

…

Strategies for Every Readventurer

(Or, How I Read 100 Classics)

- Engage in wanton book polygamy. The idea of reading several books at once used to give me an insta-headache, but The Challenge changed all that. Anyone reading books so bloated they require two epilogues, or come with an author’s apology, is bound to burn out hard and fast. I’ve learned to love “revolving door reading,” and never looked back since.

- Play it by ear. Audiobooks are the easiest way to read loads and remain lazy. You don’t even need to change your existing routine, except to press a button once in a while. And to all those who insist that “audiobooking isn’t reading,” I’d like to say this: You do you. But audiobooks, in my mind, enhance the reading experience—and they were one hell of a sidekick for 15/100 classics I tackled for The Challenge.

- Proceed not with caution, but with confidence. Even if a notoriously rabid, 800-page beast of a book with a barely pronounceable Russian name sounds mildly intimidating, ignore that initial instinct to dip a couple of dainty toes in the water. Cannonball into that book. Commit right up front. I read somewhere once that if you can dog-paddle your way through 25 pages of Ulysses per day, you’ll be done in a month. (Math agrees, and so do I.)

- Just keep reading, reading, reading. Can’t keep up with your own ambitions? There’s still hope. Success can be a sprint, but more often, it’s a marathon. Yours depends on turning just a few pages—five will do—every night before bed. I got through some of the most head-scratching, mind-boggling, brain-bruising novels this way: a little at a time.

- Use your resources. Don’t give up on that impossible read just because it’s impossible. Dial 911—a.k.a. SparkNotes, Cliff Notes, Shmoop, and the blogosphere—and ask for help. There’s always some brave hero(ine) out there waiting to save the day. Let them come to your rescue—then turn around and pay it forward.

Biggest Takeaways

(Among Countless Lessons Learned)

- Just because someone did it first does not mean they did it best. Often, it means just the opposite. So can we stop worshiping the ground trodden by Tolkien, and Lawrence, and Hemingway? Or at least acknowledge that their imagination far outstripped their implementation? No? OK. I tried.

- No book is made “classic” by accident, and we’re leaving a lot of our fellow humans out of the club. If the Literary Canon were a person, he’d be a straight, white, rich, able-bodied colonialist, probably with a beard and a monocle. He’d definitely be a he. And while his voice deserves to be heard, just like anyone else’s, the anyone elses have been patient enough. It’s the Canon’s turn to listen, and to make a little room.

- Don’t judge a book by its cover. Not even by its back cover. Plot summaries can be woefully misleading at the best of times, and tragically deterrent at the worst. There were moments during The Challenge that I fully anticipated an epic struggle with an epic hate-read (Lolita, A Clockwork Orange)—or prepared a place on my bookshelf for a brand new favorite (Wuthering Heights, Tristram Shandy)—only to be taken by surprise. But you know what? There’s a reason they call it the thrill of discovery. And it’s probably the reason we should read outside our comfort zone.

- Don’t waste time reading books you hate. This might seem counterintuitive, since I spent five and a half years doing just that. But I couldn’t agree less with that snooty Atlantic writer who thinks there’s shame in DNF’ing. I admit that I’m unable to abandon books en route, but I consider this a weakness instead of an asset. Quitting books is a habit I’d give anything to cultivate—if only to continue reading like crazy while (hopefully) remaining sane.

- There’s only one thing that makes any book Great: You. You decide. Don’t listen to any publishers, reviewers, hipsters, or lists telling you there’s anything objective about Greatness. You may not know yourself what makes you connect with one book, and shudder at another. But the good news is that nobody can tell you you’re wrong.

My Favoritest Classics of All Time

(In No Particular Order)

- One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez

- Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray

- Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

- Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy

- To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

- Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut

- Dangerous Liaisons, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

- Catch-22, Joseph Heller

- The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton

- Beloved, Toni Morrison

Works of Indisputable Genius

(Whether I Liked Them or Not)

- The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri

- 1984, George Orwell

- Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

- Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison

- Lord of the Flies, William Golding

- The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

- King Lear, William Shakespeare

- The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas

- Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

My Literary Grudges

(May Their Ink Fade Away and Their Pages Crumble to Dust)

- Rabbit, Run, John Updike (to be referred to hereafter as “The-Book-Which-Shall-Not-Be-Named”)

- Faust, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

- An American Tragedy, Theodore Dreiser

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

- Sons and Lovers, D. H. Lawrence

- Herzog, Saul Bellow

- Gargantua and Pantagruel, François Rabelais

- The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann

- The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Most Challenging of the Challenge

(Especially Difficult and/or Tedious Classics)

We should probably stop here and camp out for a while. That’s how formidable Finnegans Wake turned out to be.

For the sake of time, though, we’ll move on. Just know that there’s a boundless, hopeless chasm between the Wake and the rest of this list.

- Finnegans Wake (it bears repeating)

- Ulysses, James Joyce

- Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne

- The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner

- Absalom, Absalom!, William Faulkner

- Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

- Malone Dies, Samuel Beckett

- Moby-Dick, Herman Melville

- Nostromo, Joseph Conrad

- The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck

Buried Literary Treasures

(Books I May Never Have Read, and Loved, Without Taking on The Challenge)

- The Call of the Wild, Jack London

- All the King’s Men, Robert Penn Warren

- Go Tell It on the Mountain, James Baldwin

- The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins

- The Tale of Genji, Murasaki Shikibu

Frequently Asked Questions

(Or, More Accurately, Questions Literally No One Has Asked Me)

1. Will you read any more classics after this?

Of course. I’m even more excited to read the classics now that I know which authors to seek out (Baldwin, Morrison, Vonnegut)—and which ones to avoid like puddles on a subway platform (Updike, Steinbeck, Joyce).

2. Will you continue blogging?

That’d be a heartfelt maybe. Someday I hope to get a pet and blog about it.

3. Was The Challenge worth the time and effort?

God, no.

4. Really? Not even for the bragging rights?

I avoid discussing The Challenge as much as possible—mostly because reading The 100 Greatest Books of All Time makes me sound like an asshole. In the end, The Challenge has mostly served to fuel my reckless TBR on Goodreads (see #1) and my Christmas gift ideas for friends and family.

I mean, yeah, I read some incredible books (Lolita, Midnight’s Children, The Canterbury Tales). But whether or not those Kings Among Books outrivaled all the monsters (Tristram Shandy, Finnegans Wake, The-Book-Which-Shall-Not-Be-Named) isn’t something I’m equipped to measure.

5. What is the greatest book of all time?

That’s up to you to decide for yourself. The book that stood out to me the most among all the masterworks on The List—the book that, for me, transcended every other reading encounter I’ve ever had or expect to have—was Beloved.

6. So, what now? Book-wise?

I don’t know! And I’m trying to be OK with that.

…

And so, on my very last page, I wish you—forever and ever—happy reading. Consider yourself invited to my pie party, happening now at a bakery near you.

COME AT ME, PIE. IT’S EAT OR BE EATEN. I hope you’re up to the challenge.