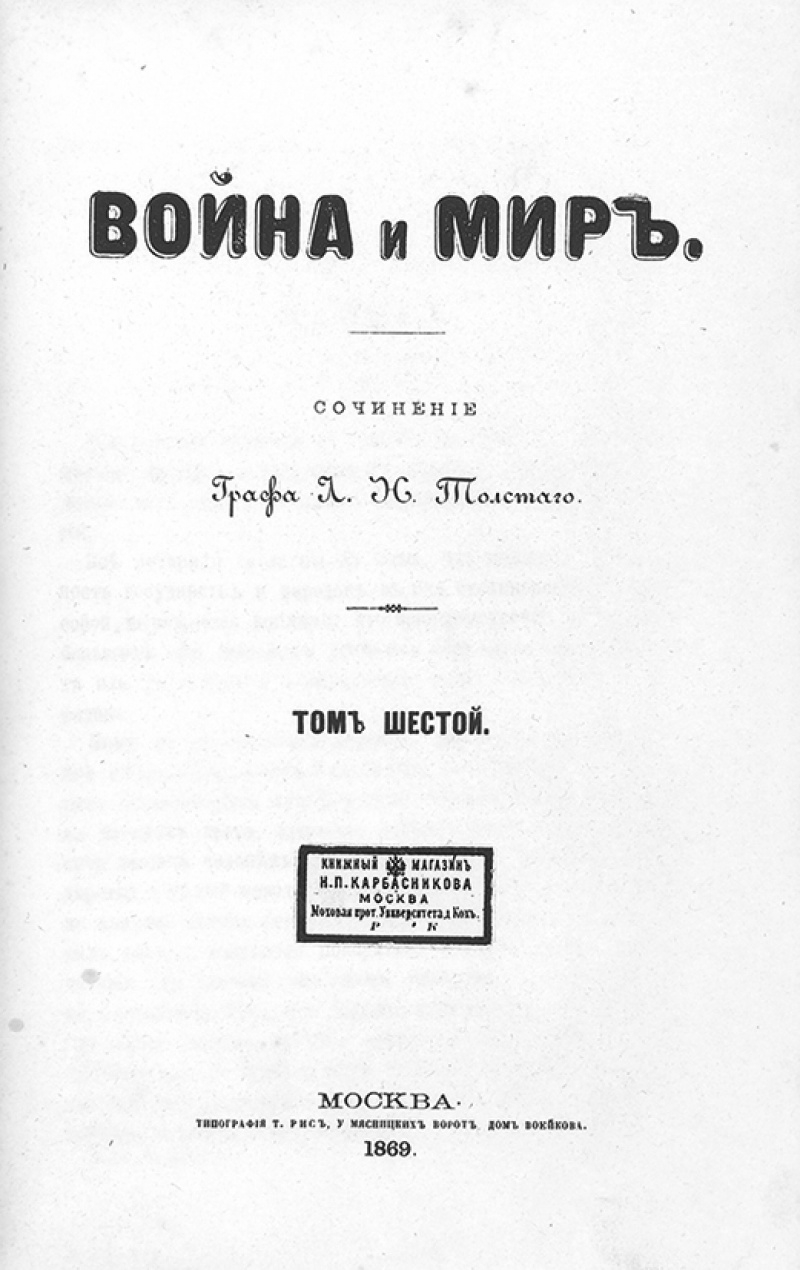

If we were looking to crown One Classic to Rule Them All—the ultimate, quintessential, indisputable classic that comes to mind whenever we hear the word—War and Peace (1865–1867) would be a reasonable candidate. Classics don’t come much bigger, broader, bolder, or better than Tolstoy’s masterpiece of realism. It tops British readers’ literary wish lists and spawns relentless adaptations. It’s about literally everything. And it’s hailed, time and time again, as one of the Greatest Books of All Time.

Which is exactly why I’m here.

Tolstoy insisted that War and Peace

is not a novel, still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle.

But the latter comes, in many ways, closest to reality. Tolstoy wrote his 600 characters against the backdrop of the French invasion of Russia in the early 1800s. And, according to Shmoop,

Tolstoy’s research didn’t just involve reading some history books and calling it a day. No, he dove into the archives, getting his hands on actual letters sent by Napoleon and the Russian and French generals and figuring out the personalities involved from the way they wrote about their activities. Even more impressive, he traveled to the actual battlefields, compass and surveying tools in hand, to map out for himself where the troops were stationed and how they attacked and defended.

War and Peace, then, was Tolstoy’s attempt to rewrite history—and, hopefully, correct it. In his mind, history was a product of diverse forces across time and place, from the greatest general and the most decisive battle to the smallest, most “insignificant” contextual detail. People don’t make history; history makes history. What came before determines what comes after.

But Tolstoy’s version of the Napoleonic era is more than a little subjective, with more than a few fictional events and characters. The main cast is made up of:

- Pierre Bezukhov, a socially inept party-boy-turned-heir-turned-Freemason-turned-politician-turned-prisoner who acts as a stand-in for Tolstoy himself

- Natasha Rostov, an “enchanting” teenager-turned-fiancée-turned-adulteress-turned-wife-and-mother whose selfish streak shifts into a self-effacing one

- Andrei Bolkonsky, an intellectually-minded soldier and father who almost marries Natasha despite being twice her age

- Nikolai Rostov, brother to Natasha, soldier for Russia, and gambling disaster with a scalding temper

- Marya Bolkonsky, Andrei’s sister, and frequent bully victim of her father and her circumstances

- Hélène Kuragin, Pierre’s beautiful wife, who may or may not be an idiot but is definitely unfaithful

With an omniscient third-person narrator at the wheel, perspective turns on a dime. And while Tolstoy can be seen and felt in the philosophy of War and Peace, he is startlingly neutral in his character depictions. These are people who aren’t always likable, who make mistakes both large and small, and who often act without explanation. It’s disorienting, in my experience. But it’s equally intriguing, on a good day.

War and Peace is best known, of course, for its size. The edition I read was 1,215 pages. If we could make one collective request of Tolstoy, we’d probably ask him to get to the point a little bit quicker—and he probably could. In what outrageous literary universe does an author need a two-part epilogue? One is usually bad enough. Two is perverse and sadistic, if you’re a) me, and b) 99 books in to The 100 Greatest Books Challenge.

…

Excess and all, War and Peace is an extraordinary achievement, and it’s easy to see why it has stood the test of time. But if I’m being totally honest (and what else is this blog for), I preferred Anna Karenina. I preferred many books on The List, actually, to the illustrious War and Peace. I would go so far as to say I’m a little disappointed by it. If War and Peace is a panorama, then I prefer a close-up. If it’s a boundless, restless ocean, then I prefer a bath tub. And if Tolstoy asks me ever again to sit back, relax, and admire the glaze on the world’s tastiest doughnut, I’ll tell him No: I’d rather sink my teeth in.

Because that’s where things start to get really good.

Is It One of the Greatest Books of All Time?

War and Peace is Great with a capital G, but I didn’t Love it with a capital L.

Favorite Quotes:

War isn’t courtesy, it’s the vilest thing in the world, and we must understand that and not play at war. We must take this terrible necessity sternly and seriously. That’s the whole point: to cast off the lie, and if it’s war it’s war, and not a game. As it is, war is the favorite pastime of idle and light-minded people.

In captivity, in the shed, Pierre had learned, not with his mind, but with his whole being, his life, that man is created for happiness, that happiness is within him, in the satisfying of natural human needs, and that all unhappiness comes not from lack, but from superfluity.

I’ve noticed that being an interesting person is very convenient (I’m an interesting person now); people invite me and tell me about myself.

Pierre’s insanity consisted in the fact that he did not wait, as before, for personal reasons, which he called people’s merits, in order to love them, but love overflowed his heart, and, loving people without reason, he discovered the unquestionable reasons for which it was worth loving them.

Read: 2017